Marcia Mead Designed Happy Communities

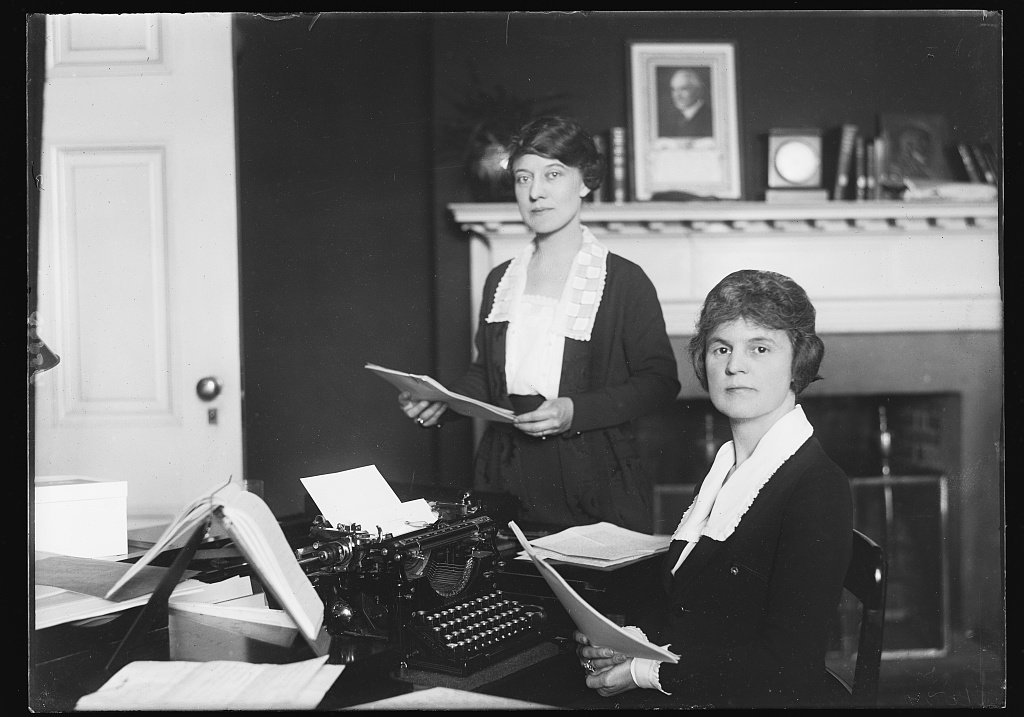

“Enthusiasm for the rights of women has led two young feminists in New York to establish the first firm of its kind in existence--a firm of women architects,” the March 8, 1914 New York Times reported of the partnership of Anna Pendleton Schenck (1874 – 1915) and Marcia Mead (1879 – 1967). In fact, Schenck & Mead were not the first partnership of “girl architects” in New York City; Gannon & Hands had opened its doors there twenty years earlier.

Partners Schenck and Mead, who in the Times article were quoted as if they were one person, said “We feel that the movement for women has gone beyond the point of argument; the thing women must have now is the opportunity to try themselves.” Schenck received her architectural education by working in architectural offices and studying in France. Mead was the first woman to graduate from the Columbia University School of Architecture. She was well-known on campus as designer for the Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds.

Women must Prove it Again. And Again.

“[W]omen and people of color are held to higher standards than white men in the profession of architecture,” the authors of the 2021 AIA/The Center for WorkLife Law investigation into bias found. To get the same level of respect or recognition, members of these underrepresented groups must work harder and longer than privileged white men. Study authors Joan C. Williams et al. found that within the architectural profession, about 42 percent of white women and 55 percent of women of color reported having to work twice as hard to receive the same level of recognition. This compares to 15 percent of white men.

This “prove-it-again” bias, in which women and members of other underrepresented groups must accomplish more to be judged as equal, is found across professions. Given the stereotypes endemic to our society, “Some groups must provide more evidence of competence to be seen as equally competent,” Williams et al. found. We link competence and maleness, another study found (DongWon Oh et al., 2018), leading to men being favored for advancement. When unrecognized and uncorrected, bias can lead to unfair hiring, performance review, work assignment, promotion, and pay practices.

Mary Colter’s Collection of Lakota Ledger Drawings

When future decorator and architect Mary E. J. Colter (1869 – 1958) was a child in St. Paul, Minnesota, a relative gave her family what she later described as “gifts from the Indians.” When word of a smallpox outbreak at the reservation reached the family, Colter’s mother feared the objects could communicate the disease to her children so she burned all the gifts. All that she found, that is.

Colter hid a group of drawings on lined paper under her mattress. “[I]t was not until many years later that my mother learned I still had them,” Colter later wrote. Colter remembered being told that these small drawings (approximately 3” x 5”) were made by (Lakota) Sioux prisoners at Fort Koegh in Montana. They were likely imprisoned for resisting the forcible taking of their lands by the US government, perhaps by fighting in the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Frances Gabe Invented a Self-Cleaning House

Inventor, builder, and artist Frances Gabe (1915 – 2016) channeled her impatience with housework into the design of a self-cleaning house. She started designing it in 1940, ended twelve years of building it herself in the 1980s, and received a patent for it in 1984. Gabe was the daughter of an architect and builder and was married to a builder for 35 years. She had a home-renovation business at one time, although she was also a talented ceramicist and jewelry-maker. Gabe’s goal with her self-cleaning house was to free up time for women to spend with their families and to allow elderly people and people with disabilities more autonomy, she told People magazine in 1982.

Gabe’s 1,000 square foot self-cleaning home has been described as a carwash or a giant dishwasher. Each room in the Newburg, Oregon house was designed with a sprinkler on the ceiling that sprayed water, with soap added to the plumbing system when needed. Surfaces were dried with jets of warm air. The wood floors were coated with multiple layers of marine varnish to protect them. The floors sloped a half inch per 10 feet to gutters at the room perimeters; water drained out through the fireplace and into the dog house, giving it (or its occupant) a wash as well. All items in the house were protected from water. For example, picture frames and book covers were water-tight, and furniture sat on castors and was upholstered with waterproof materials. The bedding and a rug were the only items that needed to be removed or protected before starting the house’s cleaning cycle.

Qualifications and Commitment: A Higher Bar for Women

When assessing candidates, employers consider not only a candidate’s qualifications for a position but also their potential commitment to it. This assessment varies with the gender of the candidate, researchers have found. Female candidates must be overqualified to be considered committed to their careers. In contrast, male candidates need only be qualified. In fact, overqualified male candidates are viewed as less committed to the potential employer, for they are expected to move on to a better opportunity after a short tenure.

This higher bar for employment for women is owing to stereotypes about gender that employers fall back on owing to the absence of applicant-specific data. These include the biased assumption that all women prioritize their family over their careers. Researchers also found that employers (like our society) expect women to act communally, prioritizing the best interest of the team over their personal ambitions. Prospective employers might also assume the overqualified female candidate is leaving her current firm for a “legitimate” reason like escaping gender bias rather than a desire to advance her career. Overqualified female employees are therefore are not considered a flight risk like their male counterparts.

Mary Colter and the Scandal of Smoking

In the late nineteenth century when Mary E. J. Colter entered the workforce, smoking was a masculine habit. Even proximity to smokers was considered disreputable for women. Where women were able to find work alongside men like at the US Patent Office, employers banned smoking in corridors and any rooms occupied by “lady employees” to protect their status and reputations. Some science and other professional associations used smoking etiquette to diminish or exclude their female members: they hosted professional dinners, after which the male members retreated to a smoking room to conduct business.

Smoking was not the only activity considered “unwomanly” in this era. Climbing ladders—a professional necessity for architects, among others—and dressing in pants also fell into this category. During her career as a decorator and architect in the early twentieth century, Colter (1869 – 1959) engaged in all of these so-called transgressions. She also used “delightfully salty” language and enjoyed alcoholic beverages.

Emily Warren Roebling and the Brooklyn Bridge

Prior to—and largely after—her involvement in building the Brooklyn Bridge, Emily Warren Roebling (1842 – 1903) was best known as a club woman. In 1900, for example, Roebling received numerous mentions in the magazine of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, but just two referenced her work on the Brooklyn Bridge. One referred to the incapacitation of her husband, the bridge’s chief engineer, before writing, “He was able…to instruct Mrs. Roebling and she completed his plans so well that it was said, ‘His work was hardly missed, so magnificently was it done by his wife.’”

Col. Washington A. Roebling, a civil war veteran, had been appointed the project’s chief engineer in 1869 when his father John A. Roebling died after contracting tetanus during his work on the bridge. Washington Roebling was prepared for the position; he had studied caisson foundations in Europe and also worked closely with his father, who had considered his son indispensable to his work.

Tightrope Bias: Another Balancing Act for Women

The most prevalent bias found in the architectural profession is tightrope bias, an AIA/The Center for WorkLife Law investigation found. Tightrope bias describes the balancing act women and minorities must play owing to societal expectations about dominance and assertiveness. “Women need to behave in masculine ways in order to be seen as competent—but women are expected to be feminine. So women find themselves walking a tightrope between being seen as too feminine to be competent, and too masculine to be likable,” Joan C. Williams, an expert on social inequality, writes in the Harvard Business Review.

This means that office politics are far more complex for women and minorities. In order to succeed, these groups need to expend more mental and emotional energy than white men. “White men just need to act competent and commanding, while members of other groups need to convey competence and leadership without triggering backlash fueled by the sense that they are behaving inappropriately—even when they do something that is readily accepted in white men,” the investigation’s authors write.

Mary E. J. Colter and Park Planning

When Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919, the National Park Service (NPS) inherited the buildings constructed prior to the park’s formation. Officials felt fortunate for what they came into at the south rim of the Grand Canyon. NPS landscape architect Charles Punchard reported finding “a certain degree of refinement and success in the design and location of structures already on the ground. The character of the building that was done under the direction of the railroad company and the Fred Harvey Co. was interesting and commendable.”

Two buildings designed by architect and decorator Mary E. J. Colter (1869 - 1958) were among those receiving accolades. They met the NPS’s competing missions of both leaving parklands “unimpaired” and providing the means for the public to enjoy the sites. By her use of rustic, native materials and integration of the structures with their sites in her 1914 designs for The Lookout and Hermit’s Rest, Colter anticipated the design priorities of the NPS which was established in 1916.

Margaret Hicks, First Published Female Architect

Margaret Hicks (1858 – 1883) was the first woman to publish her work in a professional journal and the second to earn an architecture degree from an accredited university. Her design for a workman’s cottage was published in the April 13, 1878 edition of The American Architect and Builder News. Hicks received a state scholarship to attend Cornell University where she earned a bachelor of arts degree in 1879 and a bachelor of architecture degree in 1880.

While attending Cornell, Hicks became friends with future activist and social reformer Florence Kelley. Hicks shared Kelley’s interest in social justice as demonstrated in her designing a worker’s cottage while many of her classmates’ student projects were for a wealthier clientele. An 1883 history of women in America lauded Hicks’s design skills and concern for the poor. It read in part, “The theme selected by Miss Hicks, as her Commencement Essay, was the ‘Tenement House,’ and she seemed—unlike many of the architects who have sent plans to New York for which premiums are offered—to have remembered that houses must have light and air, closets and bed-rooms.”

Role Incredulity is Incredibly Common—and Harmful

“Role Incredulity is a form of gender bias where women are mistakenly assumed to be in a supportive or stereotypically female role…rather than a leadership or stereotypically male role,” researchers Amy Diehl and Leanne M. Dzubinki write in the Harvard Business Review.

Role incredulity hurts both individuals and their companies, the researchers write. Women must spend time and energy correcting erroneous assumptions and controlling their emotional responses to them. This can cause cumulative harm. Philosopher Christina Freidlaender illustrates the impact of such slights with the example of the pain caused if you accidentally step on someone’s foot. If people have been accidentally stepping on that person’s foot all day, their foot is already in pain when you step on it. Your accidental misstep, while to your mind causing limited damage, will cause greater harm than if you were the only one stepping on that person’s foot.

Mary E. J. Colter’s ‘Geologic Fireplace’

Architect and decorator Mary E. J. Colter (1869-1958) worked off-and-on at the Grand Canyon for four decades while employed by hospitality company Fred Harvey. Attracting and entertaining guests was part of her brief, but she often achieved this with an educational flourish. In her design for the south rim’s Bright Angel Lodge, Colter integrated the geology of the Grand Canyon into the lounge’s fireplace. The rocks used in its construction were gathered from different strata of the canyon and packed out by mules led by trail guide Ed Cummings.

Colter’s goal was to reference the geology of the canyon to create an “authentic and therefore interesting” fireplace for guests. To achieve scientific accuracy, she relied on park naturalist Edwin McKee. “I know the design I want but depend entirely on you for the geology,” she wrote to him in 1935, when she also asked McKee to review the rocks collected by Cummings. “You know I am not trying to show every strata in every part of the whole canyon, - only those that occur either on the Bright Angel or the South Rim part of the Kaibab trails.”

Katherine Stinson Otero: Aviator, Builder, Designer

Katherine Stinson Otero (1891 – 1977) had two careers, the first in aviation and next in design and construction. Born in Alabama, Stinson traveled to Chicago to find someone willing to teach her to fly. In 1912, she became the fourth woman to earn a pilot’s license, and by 1913 Stinson was performing as a stunt pilot. Among many firsts, Stinson was the first woman to fly at night, to deliver air mail, and to fly in Japan and China. Stinson kept her plane well-maintained, learning about its mechanics in the process. With her mother Emma Stinson, in 1913 she founded the Stinson Aviation Company in Hot Springs, Arkansas. The company built, sold, and rented aircraft.

Gender Biases in Recruiting, and How to Reduce them

Gender biases, which can result in treating male and female job applicants differently, has a measurable impact in architecture, an AIA/The Center for WorkLife Law investigation found. Gender biases affect women’s career paths, pay, sense of belonging, and more. It can also reduce the talent pool for employers and contribute to turnover. Often the biases are unconscious and therefore hard to mitigate.

Adopting processes that result in equitable recruiting and hiring is one way to reduce biases in architecture and other professions. Some of the available tools, like training to reducing implicit biases, are similar to those used to retain existing employees, but others apply to attracting talent. Here are three things firms can do to attract female applicants:

Painting the Painted Desert Inn

Mary E. J. Colter (1869 – 1958) had been working as an artist, decorator, and architect for hospitality company Fred Harvey for forty-six years when she was tasked with modifying the interior of the Painted Desert Inn, located in what is now Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, in 1947. As she had at the Grand Canyon’s Desert View Watchtower some two hundred miles to the west of the inn, Colter engaged renowned Hopi artist Fred Kabotie to provide wall paintings.

Kabotie’s paintings at the inn included representations of the Hopi Buffalo dance and the legend related to the ceremony of collecting salt. Kabotie chose to depict the salt legend because the inn stood on lands that Hopi people traditionally travelled through as part of this ceremony.

Architect Elise Mercur Climbed Ladders

Elise Mercur (1868 – 1947) had been practicing architecture for about four years before she rose to national attention in 1894. That was the year her design was selected in a competition for the Women’s Building for the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. Thirteen women competed for the “substantial prize” offered for the best design.

The board of Lady Managers unanimously voted for Mercur’s design. A newspaper reported, “The [male] architect who conferred with the committee in regard to their choice of plans said he had no idea that women could do such artistic and practical designing and drawing.” The same man is quoted as marveling, “‘These buildings are bold enough to be drawn by men.’”

Gendered Ageism: No ‘Right Age’ for Women

Ageism is a bias that disproportionally affects women, and it affects them at every age. “Gendered ageism sits at the intersection of age and gender bias and is a double whammy where there is ‘no right age’ for professional women,” Amy Diehl et al. found in their survey of female leaders and reported in the Harvard Business Review (HBR).

Older women (defined in the study as over 60) reported feeling undervalued and overlooked for advancement opportunities. Younger female leaders (defined as under 40) and those who look young reported being condescended to and of facing “role incredulity”: being mistaken for administrative support, an intern, or other junior woman. Non-white women experienced role incredulity at even higher rates than white women. These women also often face a “credibility deficit” and have to expend energy and time to prove they know what they are talking about.

Mary Colter’s Big Break

Future architect and decorator Mary E. J. Colter (1869 – 1958) combined her talents for teaching, exhibiting art, and lecturing at women’s clubs in 1906. That was the year the General Federation of Women’s Clubs held its national biennial convention in St. Paul. Colter volunteered to serve on the host city’s Art and Decorations committees.

Colter’s role gained greater importance when a construction delay prevented the convention from being held in a new auditorium building. The Biennial was relocated to the St. Paul Armory, a building commonly occupied by National Guard troops. With help from her students, Colter transformed the military hall into a meeting space suitable for a national convention.

Gannon & Hands Solved the Tenement Problem

Mary Nevan Gannon (1867 – 1932) and Alice J. Hands (1874 – 1971) met in 1892 while studying architecture at the newly opened New York School of Applied Design for Women. “These friends work together most harmoniously, consult on every important enterprise, and are so inseparable that they are indiscriminately called Gannon or Hand by their fellow-students,” an 1896 profile of the architects read.

After completing their technical training in 1894, the women worked for two of their former instructors. These architects were in turn employed by a large firm so the work of entering design competitions was, Hands wrote, “left almost wholly to us. So largely were our suggestions accepted and so much of the work was practically ours that we decided after three out of the five plans we had worked out were awarded prizes, that instead of spending our time and energy working for others without receiving outside credit we would constitute ourselves a firm for independent work.” Gannon & Hands opened in New York in 1894 and was likely the first female architectural partnership in the U.S.

Sexual Harassment is Rampant: Help End It

Sexual harassment is common in the architecture profession. Among female architecture and construction professionals surveyed, 85 percent reported experiencing sexual harassment. Of the male survey respondents, 25 percent reported having been harassed. These percentages are roughly twice those of the overall workforce across occupations.

The most common form of harassment experienced by female architecture professionals was sexist comments (64 percent), followed by uncomfortable jokes or stories (50 percent). Unwanted physical contact was experienced by 27 percent of women, while 15 percent were faced with sexual or other inappropriate images. Women in architecture experience harassment from co-workers (58 percent of white women, 59 percent of women of color), contractors and subcontractors (49 percent of white women, 64 percent of women of color), and clients (36 percent of white women, 35 percent of women of color), the AIA/The Center for WorkLife Law investigation into bias in the architecture profession found.